This week’s featured articles are made possible thanks to the generous support of The Loppet Foundation, host of the Masters World Cup 2018. Registration opens in October.

***

Beyond the hundredth meridian, a traditional geographic line demarcating where the West begins, it’s been a hot and dry summer. Wildfires have raged from Washington to California, the Intermountain West, and in western Canada. The conditions remain ripe for extreme fire danger. Even if a wildfire didn’t burn near you, odds are the smoke found its way there.

Across the board and across the U.S., it’s been an off-the-charts summer. While many Americans have been consumed with hurricane coverage and concerns over the last several weeks, fires have scorched more than a million acres in Washington and Oregon alone this year, according to Quartz Media. That’s up from 513,226 total acres in 2016, but in 2015 and 2014, more than a million acres were affected.

Along with the devastated landscapes and loss, the wildfires’ byproducts of smoke and ash have made for smoggy, poor air quality. We’re talking about seriously hazy days when visibility often wasn’t more than a mile or two.

Training outside in less-than-ideal quality air can compromise an athlete. To better understand when it’s OK to go out or stay in, many skiers and coaches became intimate with the scientific benchmarks for air quality.

“I sort of have this rule where if I can see the glaciers on the mountain, I would rollerski but not do intervals,” Dakota Blackhorse-von Jess, who’s based out of the Bend Endurance Academy in Oregon, said on the phone last Friday. “My personal limit for being outdoors is that 75 AQI limit. That’s the unhealthy or moderate zone.”

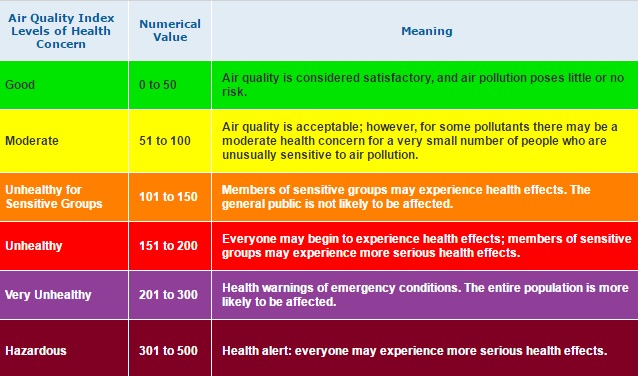

Here’s a quick primer. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed an user-friendly Air Quality Index (AQI). The index is color coded and provides a numerical value indicative of a region’s air quality. An AQI of 75 means the air has a PM2.5 concentration of 23.5 micrograms per cubic meter. Going further, PM2.5 refers to the size of particulate matter in the air. In this case, the 2.5 corresponds to particulate matter 2.5 microns or less in width. That’s small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs, even the bloodstream.

That 75 Blackhorse-von Jess limit falls midway into the moderate zone on the AQI.

“The higher end of moderate,” Blackhorse-von Jess clarified. “You see what the station says and then you walk outside and determine if it is going to work. Honestly, at this point, it’s been five weeks. I’ve done so much training indoors, that now it’s more of a mental break than a training deficiency.”

In places like Bend, Ore., where Blackhorse-von Jess calls home, some athletes have ignored the warnings.

“I saw guys out there riding today, I see them every time when I am looking for breaks in the smoke,” Blackhorse-von Jess explained. “I cannot believe that people are out there. I think people living in the smoke have accepted a lower standard and are going about their daily lives and actually, their daily activities in the smoke have come to accept the shittiness of the feeling they are experiencing. And for the professional athlete, it is something that you cannot afford, I don’t believe.”

While several fires continue to burn, the smoke cleared in Bend on Sept. 9. During much of August and into the beginning of September, Blackhorse-von Jess relied on a SkiErg, running treadmill and a stationary bike for much of his over-distance training.

He is not alone.

“Actually today, it was still dark when I woke up, but when the sun came up there was actually blue sky,” U.S. Ski Team member Liz Stephen said Friday from her home in Park City, Utah. “Where other days, you weren’t even sure the sun was up. It was really nasty.”

Like other elite skiers across the West, Stephen had made use of indoor training opportunities. The day before Stephen spoke to FasterSkier, she logged four hours on a ski treadmill at U.S. Ski and Snowboard’s Center of Excellence (COE) in Park City.

The AQI is also careful to note what are called “sensitive groups”. That can mean older adults, children, or people with lung or heart issues. Those populations must take precautions when high exertion exercise and poor air quality mix. Being responsible for junior athletes places a premium on being cautious.

For Leslie Hall, director of the Methow Valley Nordic Team in Washington state, dealing with smoke and subsequent air quality issues have been an on-and-off again affair.

“We had a bad two week period at the beginning of August and it was leading into our annual Methow PNSA [Pacific Northwest Ski Association] Camp … so we had to make the call to move the camp,” Hall wrote in an email. “We ended up going to Oakridge, Ore., for the camp and had a great camp there with 32 kids but a fire started nearby there while we were there so we had one moderately smoky day and it has since gotten much worse there.”

Like her athletic and coaching counterparts, Hall keeps an eye on air-quality websites to determine if a practice is indoors our out. But kids are kids.

“It is quite hard to keep the kids motivated and they do not enjoy the gym workouts,” Hall noted. “But during the early smoke time, we knew we were going to go somewhere else to train fairly soon so we kept that in mind. This past week was good because there are a variety of kids running and different coaches which help. Also, intensity workouts on the exercise machines help the time go by quicker. There is plenty of complaining and calls to move East, but I think all the kids realize that we are very fortunate in general and it is hard to complain when the hurricanes are decimating the south and we just have bad air for a week or so.”

Reports from Canada mirrored the smoke-filled experience of skiers in the Western part of the U.S.

According to FasterSkier’s Gerry Furseth, on Sept. 7, British Columbia’s indices for air quality deemed Fort St John and Terrace as the only locations in the province “safe” for exercise. (The Canadian AQI is based on particulate matter 2.5 microns or smaller, but uses a 1-10+ scale with “1” being low health risk and “+” very high.)

Gareth Williams, a member of Canada’s national U25 Team and a native of Kelowna, B.C., wrote in an email that the smoke was a near-constant companion this summer.

“Summer has been great for me, I spent much of it on the Haig [glacier near Canmore, Alberta] in July,” Williams explained. “I’ve been in Kelowna the whole month of August and the smoke has yet to subside, it has actually gotten much worse recently. In past years the smoke has been bad, but I have never seen it like this. … I think the smoke isn’t as bad as some people have suggested, for me it’s not the greatest worry. I will be happy once it is gone though, getting a little tired of the orange lighting and not being able to see the sun!”

Michael Somppi, who trains with the Alberta World Cup Academy (AWCA) in Canmore, altered his plans depending on conditions.

“Personally, I haven’t found the breathing to be too bad,” Somppi wrote. “That said, I am avoiding doing any hard intensity efforts on smoky days. Today was the first day (in Kelowna) I was forced to alter my training plans, as I had planned to do a rollerski time trial, and instead opted to do zone 3 because of the smoke. Even breathing semi hard felt sketchy with how bad the air quality is at the moment.”

Another member of Canada’s U25 Team, Julien Locke has literally trained above the smoke on occasion.

“I’ve been lucky in that the smoke hasn’t been too thick during most of the important training blocks so far,” Locke wrote. “I was at the Haig Glacier 4 times this summer and while we had some hazy days, for the most part, 2400m elevation was high enough to have clear skies.”

- Air Quality Index

- Alberta

- Alberta World Cup Academy

- AWCA

- Bend Endurance Academy

- British Columbia

- california

- Canadian National Team

- Center of Excellence

- Dakota Blackhorse-von Jess

- Gareth Williams

- gerry furseth

- Intermountain West

- julien locke

- Leslie Hall

- Liz Stephen

- Methow Valley Nordic Team

- Michael Somppi

- U.S. Ski Team

- Washington

- Western Canada

- Western U.S.

- Wildfire

- wildfire smoke

- wildfires

Jason Albert

Jason lives in Bend, Ore., and can often be seen chasing his two boys around town. He’s a self-proclaimed audio geek. That all started back in the early 1990s when he convinced a naive public radio editor he should report a story from Alaska’s, Ruth Gorge. Now, Jason’s common companion is his field-recording gear.